I supported critical qualitative research efforts aimed at understanding how professional team meetings could be reimagined to foster deeper human connection. My work involved designing comprehensive research approaches, facilitating stakeholder engagement, and synthesizing complex insights about interpersonal and spatial dynamics.

My research required meticulous attention to detail, strong cross-cultural communication skills, and the ability to translate nuanced observational data into strategic recommendations. By leveraging design research techniques, I helped our team develop innovative frameworks for understanding human interaction in both physical and virtual spaces.The project sought to address fundamental questions about human connection, sensory experience, and environmental interaction at multiple scales, with a particular emphasis on transforming professional collaboration practices.

Meeting (current state) vs. Meeting (preferred state)

Art, Media & Technology Team

International Remote Company

The Non-conscious as explained by N. Katherine Hayles, Duke University

The theory that informed our design interventions

"Match the vibe of the thinking to the vibe of the space?"

Research Process diagram

Animation of manager's gaze (represented by the blue line) and when participants touched technology (circles)

● Boss is the only one gesturing

● Boss is constantly surveying while others look at their screens

● interpersonal

● unconscious

● behaviors

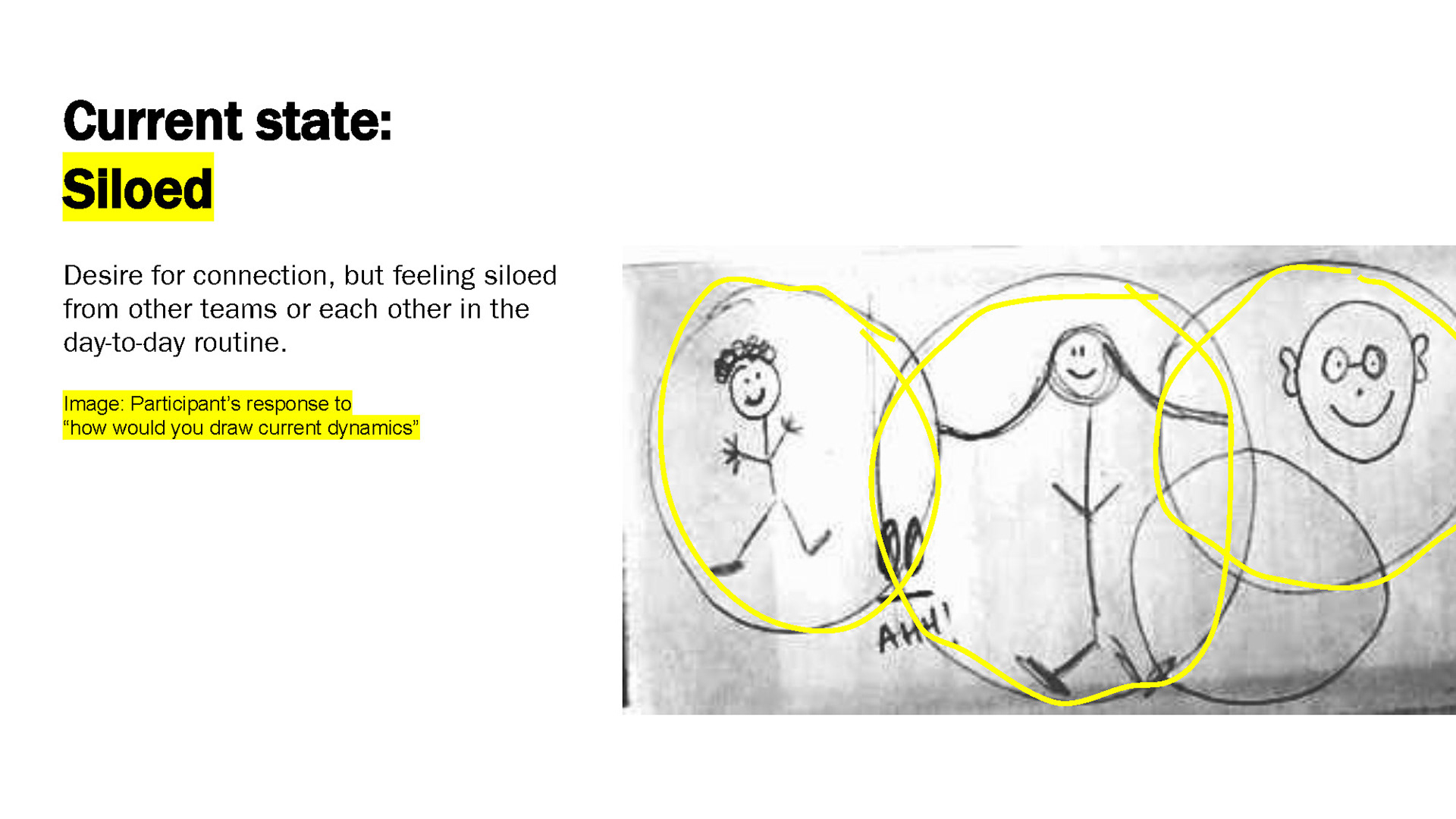

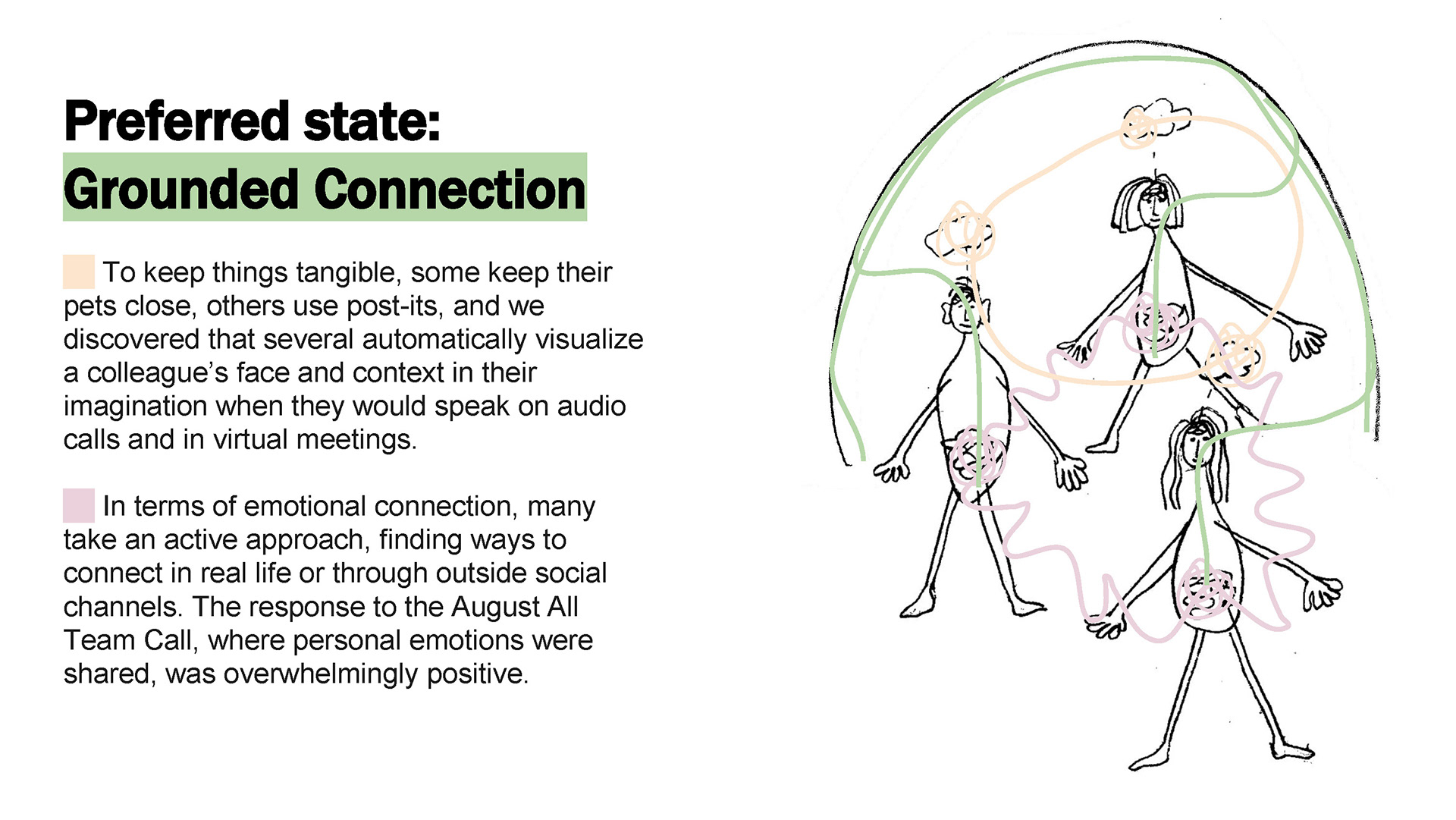

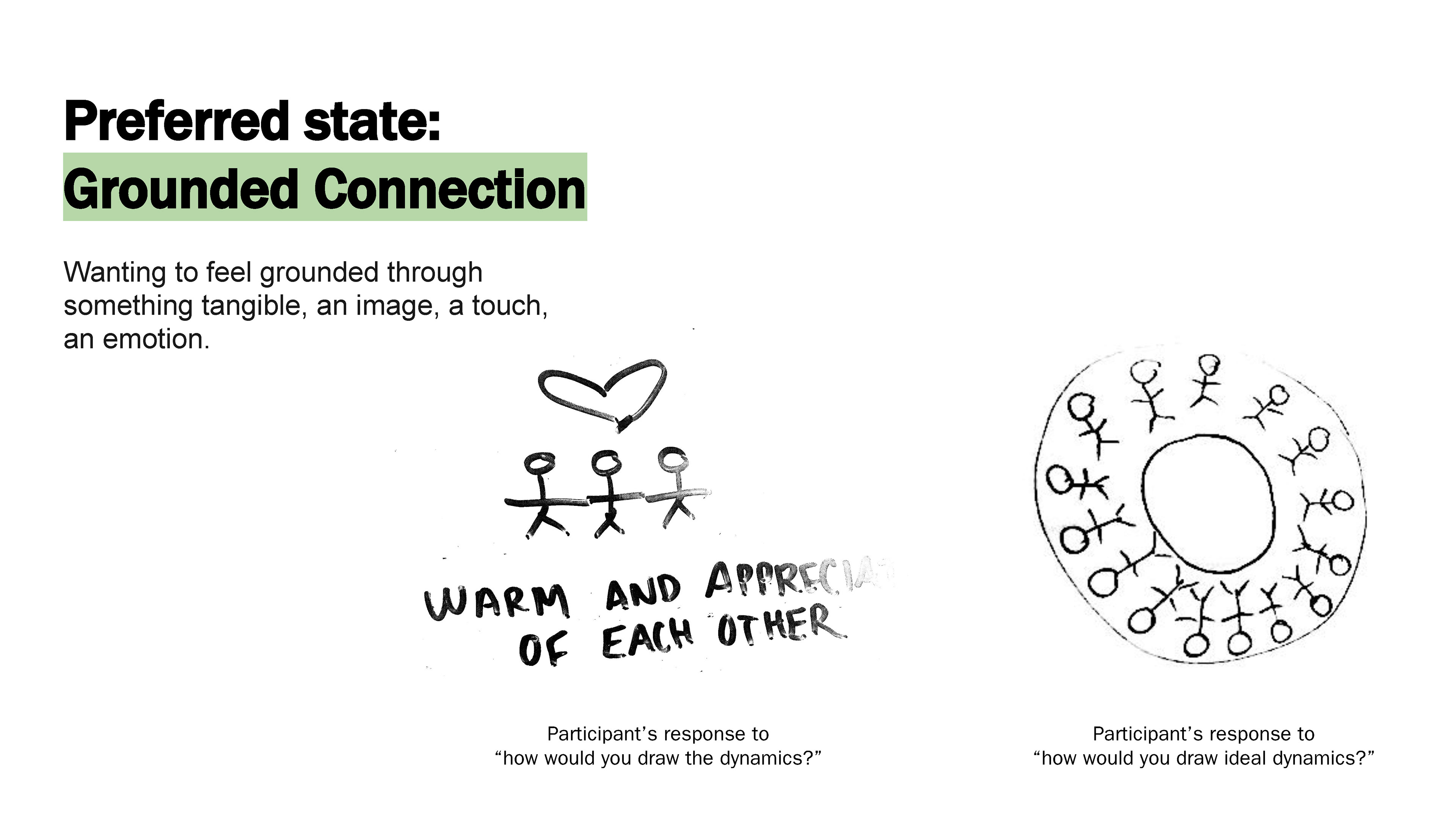

interview sketches of group dynamics in the team

Sketches from interviews about connections amongst the people on the team

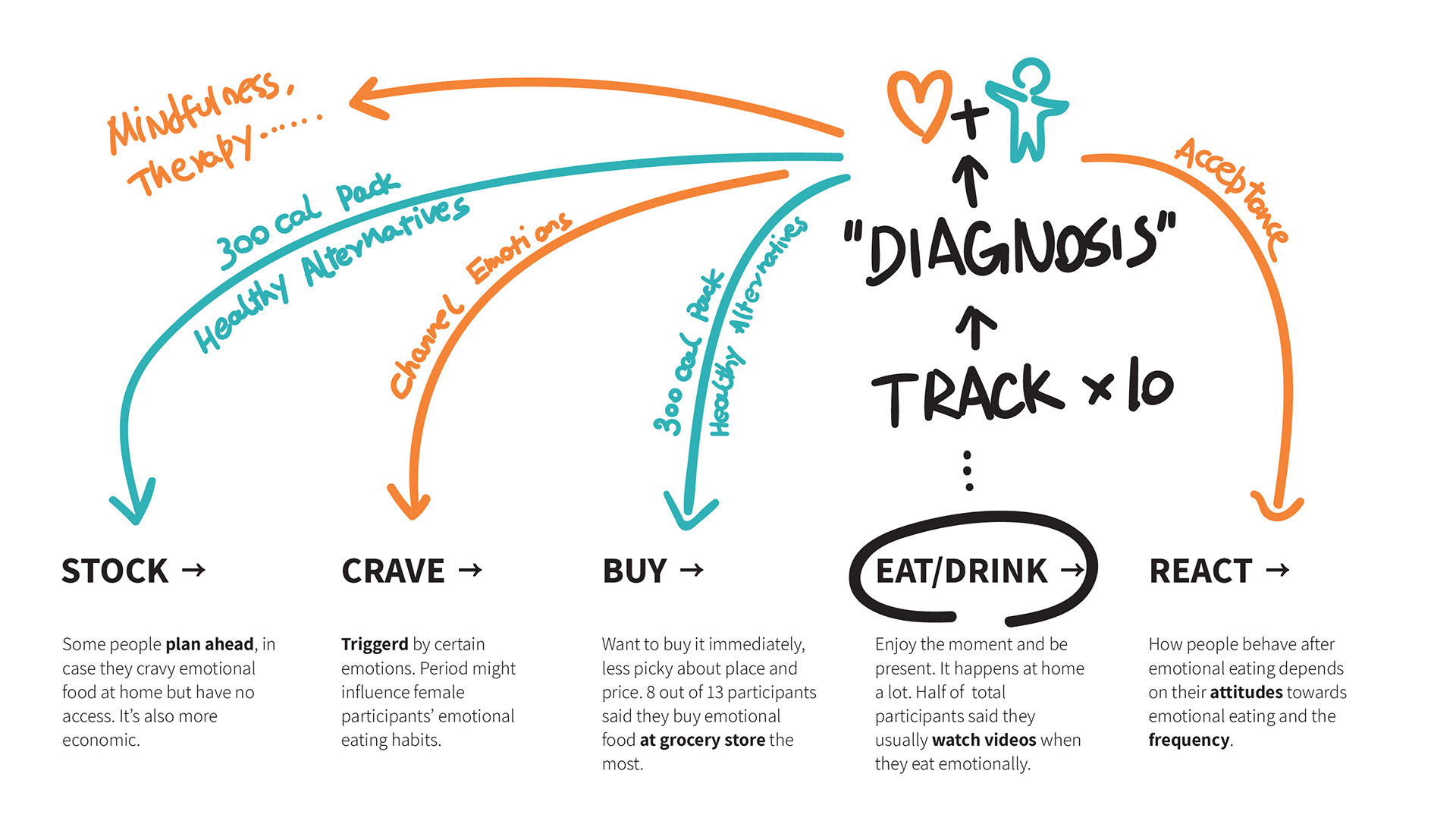

● What are the barriers preventing the achievement of the purpose?

● Positives - What’s working?

● What is the ideal state, if you were to have a meeting your way?

Mapping of the interview responses by each question

mapping research & analyzing insights

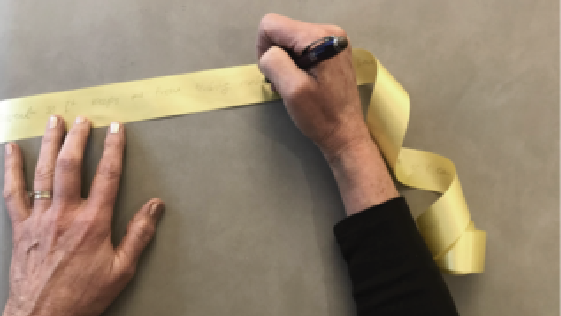

Proposed Intervention: Tie the participants' hands together

Hypothesis: This will increase the feeling of "connectedness" of the team & improve engagement

Meeting 2 with design intervention: hands are tied together around the table, laptops are closed

Research Process Diagram